Sunday 24 March 2013

Trains

Indian trains have five classes. The cheapest is seater class which consists of unreserved, metal seating. There are usually five to eight seater carriages on a forty carriage train, but they probably hold around 35 percent of the total passengers. They sit on the seats, floor, overhead luggage racks and hang out of the open doors.

The next class, in both price and occupancy, is sleeper class. Three tier bunks fold down to form seats in the day. There are no blankets or pillows and night, and the air conditioning consists of a fan placed very close to the head of the person on the top bunk. Seats are supposed to be reserved, but this is generally ignored, particularly in the day when five or six people sit on the three person bench. If you have a bottom bunk it is not unusual to wake up with someone sitting at, or even on, your feet. There are normally around fifteen sleeper carriages. This is the class we have been taking for short (five hour) journeys. It is also the class we thought we had taken on our first train journey from Mumbai to Goa.

The class we had actually taken was 3AC, short for 'Three Tiered. Air-Conditioned'. It is arranged in the same way as sleeper class, but the reservations are kept to. You are given pillows, sheets and blankets - which you need, as the air conditioning is sometimes even too cold. There are usually eight to ten 3AC carriages, filled mostly with families and single women.

Having mixed 3AC up with sleeper class, I couldn't understand why anyone would pay more for the next class up . We unfortunately didn't figure out the difference until our first over night journey - twelve hours from Cochin to Chennai, for which we had booked sleeper. We waited a long time for our blankets, which never turned up, and we didn't get much sleep because of the open train doors letting in the thundering sound of passing trains. An up grade was 'not possible madam' - except for the price of 2500rs (five times the price of a 3AC ticket in the first place). At one point we considered sleeping in shifts, because of the suspicious looking man who spent the first hour of the journey starring up at us. Fortunately he got off at the next stop, at which point I felt guilty for assuming the worst of him. We slept curled around our rucksacks and were woken by the singing, chatting and loud phone conversations of the twenty people sitting on the eight seats below us. At least we had booked top bunks.

The next class up is 2AC. This is the class we are booked in for our thirty hour train journey to Kolkata tomorrow (1AC was fully booked). Bunks are arranged in a similar way to sleeper and 3AC, but only two high, meaning there is space to sit up on your bed, and fewer people in a compartment. There are usual five 2AC carriages on a forty carriage train.

1AC consists of private compartments of two or four bunks. There is a bell to call an attendant, who can bring more blankets or direct the required food vendor to your compartment. I have heard rumors of included meals, carpets and even tvs in 1AC, but the ones I have peeked into are as basic as 3AC, just private. I think we will still try and upgrade for our journey tomorrow.

The next class, in both price and occupancy, is sleeper class. Three tier bunks fold down to form seats in the day. There are no blankets or pillows and night, and the air conditioning consists of a fan placed very close to the head of the person on the top bunk. Seats are supposed to be reserved, but this is generally ignored, particularly in the day when five or six people sit on the three person bench. If you have a bottom bunk it is not unusual to wake up with someone sitting at, or even on, your feet. There are normally around fifteen sleeper carriages. This is the class we have been taking for short (five hour) journeys. It is also the class we thought we had taken on our first train journey from Mumbai to Goa.

The class we had actually taken was 3AC, short for 'Three Tiered. Air-Conditioned'. It is arranged in the same way as sleeper class, but the reservations are kept to. You are given pillows, sheets and blankets - which you need, as the air conditioning is sometimes even too cold. There are usually eight to ten 3AC carriages, filled mostly with families and single women.

Having mixed 3AC up with sleeper class, I couldn't understand why anyone would pay more for the next class up . We unfortunately didn't figure out the difference until our first over night journey - twelve hours from Cochin to Chennai, for which we had booked sleeper. We waited a long time for our blankets, which never turned up, and we didn't get much sleep because of the open train doors letting in the thundering sound of passing trains. An up grade was 'not possible madam' - except for the price of 2500rs (five times the price of a 3AC ticket in the first place). At one point we considered sleeping in shifts, because of the suspicious looking man who spent the first hour of the journey starring up at us. Fortunately he got off at the next stop, at which point I felt guilty for assuming the worst of him. We slept curled around our rucksacks and were woken by the singing, chatting and loud phone conversations of the twenty people sitting on the eight seats below us. At least we had booked top bunks.

The next class up is 2AC. This is the class we are booked in for our thirty hour train journey to Kolkata tomorrow (1AC was fully booked). Bunks are arranged in a similar way to sleeper and 3AC, but only two high, meaning there is space to sit up on your bed, and fewer people in a compartment. There are usual five 2AC carriages on a forty carriage train.

1AC consists of private compartments of two or four bunks. There is a bell to call an attendant, who can bring more blankets or direct the required food vendor to your compartment. I have heard rumors of included meals, carpets and even tvs in 1AC, but the ones I have peeked into are as basic as 3AC, just private. I think we will still try and upgrade for our journey tomorrow.

Arriving in Cochin

Exactly eight hours after leaving Ooty, we get off the bus in Fort Cochin. Trying to hold my temper and politely say no to all the touts beckoning us into their restaurants (a 70 litre rucksack isn't really appropriate dinner attire), we head to a hostel recommended in the guide book which has dorm beds for only 200rs. We soon see why. The dorm is on the flat roof of the hostel. There is a corrugated iron awning, knee high walls around the edge and netting between the walls and the 'roof'. I am so tired that I am tempted to put up with the heat, noise and mosquitoes for a night, but thankfully Alex isn't.

Two Swedish girls I met in Mumbai who were heading to Cochin had mentioned a hostel that they were going to stay in. I didn't know where it was, and only knew that it was called something along the lines of 'The Avanta Good Morning'. I try this name out on several rickshaw drivers, all of whom stare at me blankly, until one of the near by restaurant workers over hears us. He tells a rickshaw driver the name of the hostel (The Vedanta Wake Up), gives him directions and negotiates a cheap fare for us. We thank him and promise that we will come back to eat after we have settled in.

The Vedanta Wake Up is the most luxurious place I have stayed in so far. Even though a bed in a dorm room is 500rs each, we get free wifi, air conditioning, a common room with a tv and book swap, loo roll, towels, soap and sheets. There is even an actual shower cubical in the bathroom, instead of a shower head in the middle of the wall which soaks everything.

After showering and changing we head back to the restaurant where we are greeted by a surprised Aadi. He obviously didn't think we were going to come back, which is understandable when I think of all the times I have said to a shop keeper or waiter 'maybe tomorrow'. Whilst I couldn't say that people in India don't try to be helpful, they usually aren't. It is a relief to have found someone who gives practical and useful advice and so I am happy to come back. The cafe is called 'Cafe Delmar' and has a view of Cochin's famous Chinese fishing nets. Aadi gives us his business card which says 'Cafe Delmar - Reggae Cafe - We do all kinds of group foods'. There is nothing particularly reggae about the cafe, excpet for Aadi's Bob Marley t-shirt, knitted beanie, and singing 'Don't worry, be happy' as he lights mosquito coils around our feet.

Monday 18 March 2013

Ooty & Indian Treasure Hunts

As the bus climbs further up the mountain the air gets cooler and cooler. I am wedged between Alex on my right and my bag, which is on the floor - my feet on top and my knees almost up to my chin. After five hours of hair pin bends we arrive in the 'Queen of Hill Stations', Ooty, also called Snooty Ooty.

'Discovered' by the Brisish in the 18th century and built up as elite holiday retreat from the heat of the cities, Ooty has a golf course, race track, boating lake and botanical garden. Thankfully for us it also has a YWCA, which is so far the cheapest, cleanest and all round nicest place we have stayed so far. Set in large grounds back from the main road, the beds have sheets and blankets and I am very excited at the prospect of needing to wear a jumper in the evening.

We spend the afternoon on the sort of treasure hunt which is becoming more and more a part of life in India. We are looking for the tourist office. Here is how to find something in India:

1. Go to where the guide book says it is.

2. When its not there, which it probably won't be because its moved or was never there in the first place, you ask someone standing near by (there will be plenty of people to choose from).

3. When the person you pick doesn't understand, keep asking until someone over hears and offers their advice (which will happen fairly quickly).

4. Follow their directions. Sometimes you will helpfully be taken there, and you have to politely pretend that 'there' is where you want to be. Repeat steps two and three.

5. Eventually you will find what you thought you were looking for, usually to be told you're at the wrong tourist office/bank/bus stand/post office and steps two and three need to be repeated again.

6. Persevere!

When we find the right tourist office - the first didn't book tours and in the second there was no one who spoke English - we manage to book a day long tour of the local area, ending in a trip to the Mundalami Wildlife Sanctuary. We are told we will have an English speaking guide and the only extra we will have to pay is entry to the wildlife sanctuary. I am very excited and feel sure that I will see a tiger despite everyone's claims that 'its possible, but probably not'.

'Discovered' by the Brisish in the 18th century and built up as elite holiday retreat from the heat of the cities, Ooty has a golf course, race track, boating lake and botanical garden. Thankfully for us it also has a YWCA, which is so far the cheapest, cleanest and all round nicest place we have stayed so far. Set in large grounds back from the main road, the beds have sheets and blankets and I am very excited at the prospect of needing to wear a jumper in the evening.

Above : Our room at the YWCA

We spend the afternoon on the sort of treasure hunt which is becoming more and more a part of life in India. We are looking for the tourist office. Here is how to find something in India:

1. Go to where the guide book says it is.

2. When its not there, which it probably won't be because its moved or was never there in the first place, you ask someone standing near by (there will be plenty of people to choose from).

3. When the person you pick doesn't understand, keep asking until someone over hears and offers their advice (which will happen fairly quickly).

4. Follow their directions. Sometimes you will helpfully be taken there, and you have to politely pretend that 'there' is where you want to be. Repeat steps two and three.

5. Eventually you will find what you thought you were looking for, usually to be told you're at the wrong tourist office/bank/bus stand/post office and steps two and three need to be repeated again.

6. Persevere!

When we find the right tourist office - the first didn't book tours and in the second there was no one who spoke English - we manage to book a day long tour of the local area, ending in a trip to the Mundalami Wildlife Sanctuary. We are told we will have an English speaking guide and the only extra we will have to pay is entry to the wildlife sanctuary. I am very excited and feel sure that I will see a tiger despite everyone's claims that 'its possible, but probably not'.

Young Women in India

Across the road from our rooftop resturant in Mysore there is a ladies department store. Even though it is 8:30 at night the store is still open and very busy. From our high vantage point we can see through the big windows into each of the four floors where they are selling saris, shawls and 'salwar kameezs' - baggy trousers, tight at the ankles, with a long top and matching scarf. After our dinner we go in and look around. The walls are lined with shelves from floor to ceiling and they are filled with different coloured fabrics. In front of the shelves there are long, low display cabinets, like in an old fashioned department store, with shop girls standing behind them waiting to serve you.

This is the first time I have seen women working in public - all the street vendors, bus drivers and waiters are men. Their supervisor or manager however, is a man. He does lots of shouing at the girls doing the work. A shop girl comes up to us shyly after watching us for a while. She looks about 18 and asks our names, giggling as she trys to pronounce 'Imogen'. Her name is Narayani, which she says is another name for the Goddess Durga. She asks if Alex is married, and points to her feet, telling us that wearing a toe ring means that a girl is married. Alex laughs and says 'No, i'm too young!', then asks if Narayani is married. She laughs even louder than Alex did and says that no, she is also too young. She shows us around each floor, getting out lots of scarves and saris. She says that Indian women buy a new sari for every special occasion, and that it is very embarassing to wear the same one twice. Indian attics are full of boxes and boxes of saris all worn only once.

On the top floor, which is empty of customers, there is a group of about six girls sitting on the display cabinets. They stop talking when we walk in and stare at Narayani before asking her lots of quesions all at once. Narayani hushes them, and tells us proudly that the girls are all her friends. She introduces them to us and vice versa. I ask them if they enjoy working there, and they all nod and start talking at once. One of them notices my nose stud - 'like Indian woman'. I feel very not like an Indian woman. They are all beautifully dressed, with lots of jewellery and I am tired and hot with dirty feet and wearing what probably looks to them like pyjamas. I feel like I am not living up to their image of a western girl is like, or at least what I think their image of a western girl is - they are probably used to grubby travellers.

One of the girls then notices the tattoo on Alex's foot, gasps, and starts whispering to the girl next to her, who looks and exclaims 'you have a tattoo!'. I ask if they like tattoos and they say 'no, they are horrible!' and I laugh and agree. We leave the store with lots of good byes, waving, hand shakes and more pointing at the tattoo. Alex and I agree that, after a horrible 24 hours of buses and being ripped off, the past half hour has rekindled what was a dwindling intrest in all things India.

This is the first time I have seen women working in public - all the street vendors, bus drivers and waiters are men. Their supervisor or manager however, is a man. He does lots of shouing at the girls doing the work. A shop girl comes up to us shyly after watching us for a while. She looks about 18 and asks our names, giggling as she trys to pronounce 'Imogen'. Her name is Narayani, which she says is another name for the Goddess Durga. She asks if Alex is married, and points to her feet, telling us that wearing a toe ring means that a girl is married. Alex laughs and says 'No, i'm too young!', then asks if Narayani is married. She laughs even louder than Alex did and says that no, she is also too young. She shows us around each floor, getting out lots of scarves and saris. She says that Indian women buy a new sari for every special occasion, and that it is very embarassing to wear the same one twice. Indian attics are full of boxes and boxes of saris all worn only once.

On the top floor, which is empty of customers, there is a group of about six girls sitting on the display cabinets. They stop talking when we walk in and stare at Narayani before asking her lots of quesions all at once. Narayani hushes them, and tells us proudly that the girls are all her friends. She introduces them to us and vice versa. I ask them if they enjoy working there, and they all nod and start talking at once. One of them notices my nose stud - 'like Indian woman'. I feel very not like an Indian woman. They are all beautifully dressed, with lots of jewellery and I am tired and hot with dirty feet and wearing what probably looks to them like pyjamas. I feel like I am not living up to their image of a western girl is like, or at least what I think their image of a western girl is - they are probably used to grubby travellers.

One of the girls then notices the tattoo on Alex's foot, gasps, and starts whispering to the girl next to her, who looks and exclaims 'you have a tattoo!'. I ask if they like tattoos and they say 'no, they are horrible!' and I laugh and agree. We leave the store with lots of good byes, waving, hand shakes and more pointing at the tattoo. Alex and I agree that, after a horrible 24 hours of buses and being ripped off, the past half hour has rekindled what was a dwindling intrest in all things India.

Hampi to Mysore

After we have had our fill of temples in Hampi we head to Ooty. To get there we take an awful awful ten hour over night bus to Mysore. The road is so bad that everytime we hit a pot hole (which is every two minutes) I bounce inches in the air off the bed and hit my knees/eblows/head on the sides of my little compartment. An hour in we stop once - in a one horse town with no loos, not even in the 'hotel' - and I throw up in the gutter. For the next nine hours I just have to suffer in silence - with the occasional whine when we hit a particularly big hole.

We arrive in Mysore at 7 in the morning and begin to walk to the nearest hostel our book recommemds, but we can't find it. Alex asks a rickshaw driver where it is whilst I, exhausted and still feelig nausous, lean pathetically against a near by wall. The driver tells us the hostel is not in walking distance, and offers to take us there for '40 rupees minimum, less is not possible madam'. We get him down to 30, suspecting we are still being ripped off, but not caring much.

The room is expensive but again we don't care, it has beds, a shower and a tv. The tiny lift up to the third floor brings back horrible memories of my little bus compartmemt. I go out to buy a big bottle of water and a bigger bottle of Pepsi, and we spend the morning sleeping, rehydrating and watching movies. The power goes off reguarly for about 20 minutes at a time, which confims my decision to use the stairs.

In the afternoon we venture out and walk to a near by market. We get to the end of the road before we are too hot and too tired, so we take a rickshaw. It costs us 20 rupees and takes us well past the bus stand, so we had definitely been conned by our driver this morning, he must have driven around the block a couple of times to make it seem further. Mysore is hot, loud and busy and I am really looking forward to moving onto Ooty in the morning. We book tickets for the five hour journey for 8am the next day at 100 rupees each (about £1.50), then find a roof top terrace where Alex has dinner and I drink another pepsi.

We arrive in Mysore at 7 in the morning and begin to walk to the nearest hostel our book recommemds, but we can't find it. Alex asks a rickshaw driver where it is whilst I, exhausted and still feelig nausous, lean pathetically against a near by wall. The driver tells us the hostel is not in walking distance, and offers to take us there for '40 rupees minimum, less is not possible madam'. We get him down to 30, suspecting we are still being ripped off, but not caring much.

The room is expensive but again we don't care, it has beds, a shower and a tv. The tiny lift up to the third floor brings back horrible memories of my little bus compartmemt. I go out to buy a big bottle of water and a bigger bottle of Pepsi, and we spend the morning sleeping, rehydrating and watching movies. The power goes off reguarly for about 20 minutes at a time, which confims my decision to use the stairs.

In the afternoon we venture out and walk to a near by market. We get to the end of the road before we are too hot and too tired, so we take a rickshaw. It costs us 20 rupees and takes us well past the bus stand, so we had definitely been conned by our driver this morning, he must have driven around the block a couple of times to make it seem further. Mysore is hot, loud and busy and I am really looking forward to moving onto Ooty in the morning. We book tickets for the five hour journey for 8am the next day at 100 rupees each (about £1.50), then find a roof top terrace where Alex has dinner and I drink another pepsi.

Sunday 17 March 2013

Hampi

Our first afternoon in Hampi, after dumping our bags and showering, we decide to rent a motor bike to explore the temples on our side of the river, the roads are much quieter here than Goa and I practice (to lots of shouts of "Hey, you're not so good!") up and down the lane a few times before we head off. It is amazing to have the freedom of our own transport, instead of relying on buses or haggling with rickshaw drivers whenever we want to go anywhere.

We drive to the next town, Anegondi, stopping at temples on the way. The country side is surreal, I think it looks like the rice fields of China have been dropped in an Arizona golf resort. Lush green fields fill the strech of land between the river and the seemingly gravity defying arid boulders.

In the evening we drive to the Hanuman temple, also known as the monkey temple because (as the tourists say) it is crawling with monkeys and because (as the locals say) Hanuman is the monkey God in Hinduism. A winding path of 560 steps (the reason we decided to climb it in the evening) leads us to a white washed temple with a red dome. There is chanting coming from inside and monkeys on the roof. There are also monkeys on the walls, in the trees, on the surrounding rocks and sorting through the piles of shoes at the top of the steps. They enjoy taking drinks bottles from unsuspecting tourists and pouring the contents into their upturned mouths. I can hear the pilgrims below calling God's name as they climb to the top. One shouts 'Jaishriram!' and the others respond; 'Jaishriram!'. I settle down on a rock to watch the sun set, which promptly disappears behind clouds, then make the treacherous walk back down the mountain in the semi darkness.

We spend the next two days exploring a tiny handful of the 3000 the temples spread over 26 kilometres on the town side of the river. Originally called Vijayanagar, 'the city of victory', Hampi was developed mostly in the 14th and 15th centuries, before being destroyed in a six month Muslim siege in the 16th century. What remains is in poor condition and looks a lot older than it is. One of the temples is still active and is where we meet Lakshmi the elephant (no photos allowed unfortunately). The guide book says that if you give her a rupee, she will bless you with her trunk. She seems to be able to spot tourists as she gives my coin back to me and her trainer says it has to be a note not a coin. This is despite the pilgrims next to us putting a coin in her trunk and recieving not so much a blessing as a of clip round the ear.

We do manage to get a glimpse of Lakshmi coming down the steps for her bath in the river one morning, but the boat won't leave until it is full and, despite only seating about twelve, this takes a long time as they fill the boat until just before it sinks. When we get to the other side we can't stay and watch as we are late for the bike tour we booked in order to see some of the temples further out of town, including the elephant stables and the queen's bath (the size of a swimming pool). It is fun to ride the gear-less bikes down, if not up, the hills.

We drive to the next town, Anegondi, stopping at temples on the way. The country side is surreal, I think it looks like the rice fields of China have been dropped in an Arizona golf resort. Lush green fields fill the strech of land between the river and the seemingly gravity defying arid boulders.

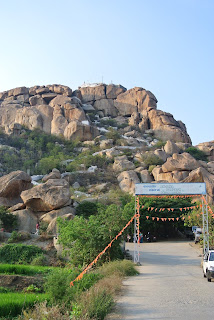

In the evening we drive to the Hanuman temple, also known as the monkey temple because (as the tourists say) it is crawling with monkeys and because (as the locals say) Hanuman is the monkey God in Hinduism. A winding path of 560 steps (the reason we decided to climb it in the evening) leads us to a white washed temple with a red dome. There is chanting coming from inside and monkeys on the roof. There are also monkeys on the walls, in the trees, on the surrounding rocks and sorting through the piles of shoes at the top of the steps. They enjoy taking drinks bottles from unsuspecting tourists and pouring the contents into their upturned mouths. I can hear the pilgrims below calling God's name as they climb to the top. One shouts 'Jaishriram!' and the others respond; 'Jaishriram!'. I settle down on a rock to watch the sun set, which promptly disappears behind clouds, then make the treacherous walk back down the mountain in the semi darkness.

Above: The climb up-to the Hanuman Temple

Above: Views from the Hanuman Temple

We spend the next two days exploring a tiny handful of the 3000 the temples spread over 26 kilometres on the town side of the river. Originally called Vijayanagar, 'the city of victory', Hampi was developed mostly in the 14th and 15th centuries, before being destroyed in a six month Muslim siege in the 16th century. What remains is in poor condition and looks a lot older than it is. One of the temples is still active and is where we meet Lakshmi the elephant (no photos allowed unfortunately). The guide book says that if you give her a rupee, she will bless you with her trunk. She seems to be able to spot tourists as she gives my coin back to me and her trainer says it has to be a note not a coin. This is despite the pilgrims next to us putting a coin in her trunk and recieving not so much a blessing as a of clip round the ear.

We do manage to get a glimpse of Lakshmi coming down the steps for her bath in the river one morning, but the boat won't leave until it is full and, despite only seating about twelve, this takes a long time as they fill the boat until just before it sinks. When we get to the other side we can't stay and watch as we are late for the bike tour we booked in order to see some of the temples further out of town, including the elephant stables and the queen's bath (the size of a swimming pool). It is fun to ride the gear-less bikes down, if not up, the hills.

Above: Lakshmi the elephant coming down for her bath.

Above: Lakshmi lying in the river.

Above: The main temple.

Above: More temples!

Arriving in Hampi

Having taken the night bus (a very bumpy ride in little pods arranged similarly to the train but more claustrophobic), we arrive in Hampi on what is called the 'other' side of the river. We walk down to the river to see the other, other side, which is home to the town, Hampi bazaar, and the main temple. The sun is rising over the boulders between which the river runs, and across the water I can see hundereds of people walking down a massive flight of steps to wash in the river; women on the left, men on the right. They are all carrying bags of laundry which they wash and beat on the rocks. From the temple we can hear singing and chanting which bounces of the surrounding rocks. This is what we came for, not tourist filled beaches. We decide to cross and find accommodation in town to save paying for the boat over every day, although the side we are on is dedicated almost exclusively to traveler hostels. The boat costs 10 rupees and 5 for a bag and it takes less than a minute to cross the small stretch of water. When we get to the other side we walk up the steps against the flow of people coming the other way.

In Mumbai a fellow traveller who had just come from Hampi told us that, when she was there, all the illegal buildings in the bazaar (which is most of them) were knocked down, but were being rebuilt as she left. We don't see any evidence of rebuilding as we walk around the small town and the new ruins don't relly measure up to the old ruins the town is famous for. Mabe in 1000 years people will be coming to see them as well. Pobably not. In the small part of town that is left we can't find accommodation for less than 600rupees a night, and we head back to the 'other' side where we get a hut with an attached bathroom for 400. The major selling point is the terrace cafe with views over the river and a breeze.

Above: Across the river

In Mumbai a fellow traveller who had just come from Hampi told us that, when she was there, all the illegal buildings in the bazaar (which is most of them) were knocked down, but were being rebuilt as she left. We don't see any evidence of rebuilding as we walk around the small town and the new ruins don't relly measure up to the old ruins the town is famous for. Mabe in 1000 years people will be coming to see them as well. Pobably not. In the small part of town that is left we can't find accommodation for less than 600rupees a night, and we head back to the 'other' side where we get a hut with an attached bathroom for 400. The major selling point is the terrace cafe with views over the river and a breeze.

Above: The view from our hostel

Sunday 10 March 2013

Palolem, Goa

We chose Palolem beach in Goa because other travelers had told us that it was more chilled out than other beaches in Goa. Our guide book described it as 'paradise'. It was neither.

The main street is lined with shops, all selling the same things - bags, jewelry, clothes and wooden boxes. There seems to be no concept of the gap in the market. There are a few cafes serving fruit juices, pancakes and omelets. One, called 'Little World' - wedged in an alley and run by a mad, long haired, shirtless Indian and his sari clad Dutch wife - claims to serve the best chai in India. Its ok, too much ginger and too much dancing from the mad owner.

The strip of land between the beach and the main street consists of a labrythn of paths winding around palm trees, bamboo huts and out-door kitchens with wood fires. Pigs, chickens and goats roam around the coralls of cheaper beach huts (no sea view). These huts are occupied by the 'long stay' travellers, who stay for the entire season, and don't seem to do much except sit on their porches all day and smoke. In the evenings the sounds of stray dogs fighting are added to the thud of coconuts falling on tarpaulin roofs and the distant beat of music from the beach bars.

Resturants serving Italian, Mexican, Israeli, lots of fish and some Indian strech from one end of the mile long beach to the other. They all have wicker chairs and tables and play rave music until the 22:00 amplified music curfew. In the evenings the sun loungers come in and the tables go out. Hoards of sun burnt tourists sit in rows facing the sea, drinking cocktails and eating the catch of the day.

It may not sound so awful but it is not what we were expecting. Too many people! It seems like a good holiday location - a little bubble where all the menus are in English and women can walk around in shorts - but not great for travelling and seeing 'the real India'. We had originally itended to stay for 5 days. After breakfast in one beach resturant, politley refusing pleads to visit every shop on the high street, a swim, lunch in another resturant (exactly the same as the first), walking the length of the beach and then onto the next beach, we realise we have done everything there is to do and plan to leave as soon as possible. In the evening we watch the film 'The Life of Pi' in an outdoor cinema and the next day book the over night bus to Hampi. It leaves on saturday, so we have some time to kill. The next two days are spent swimming, reading, sunbathing in short bursts until the sun gets to hot and we have to run to the nearest bar, our feet burning on the sand. We eagerly plan the next few weeks. I feel guilty for wasting travelling time on the beach, and slightly less guilty for wanting to leave 'paradise' as soon as possible.

The main street is lined with shops, all selling the same things - bags, jewelry, clothes and wooden boxes. There seems to be no concept of the gap in the market. There are a few cafes serving fruit juices, pancakes and omelets. One, called 'Little World' - wedged in an alley and run by a mad, long haired, shirtless Indian and his sari clad Dutch wife - claims to serve the best chai in India. Its ok, too much ginger and too much dancing from the mad owner.

The strip of land between the beach and the main street consists of a labrythn of paths winding around palm trees, bamboo huts and out-door kitchens with wood fires. Pigs, chickens and goats roam around the coralls of cheaper beach huts (no sea view). These huts are occupied by the 'long stay' travellers, who stay for the entire season, and don't seem to do much except sit on their porches all day and smoke. In the evenings the sounds of stray dogs fighting are added to the thud of coconuts falling on tarpaulin roofs and the distant beat of music from the beach bars.

Above: Alex on the porch of our beach hut

Above: Palolem Beach from a distance

Resturants serving Italian, Mexican, Israeli, lots of fish and some Indian strech from one end of the mile long beach to the other. They all have wicker chairs and tables and play rave music until the 22:00 amplified music curfew. In the evenings the sun loungers come in and the tables go out. Hoards of sun burnt tourists sit in rows facing the sea, drinking cocktails and eating the catch of the day.

Above: Cows on the beach

It may not sound so awful but it is not what we were expecting. Too many people! It seems like a good holiday location - a little bubble where all the menus are in English and women can walk around in shorts - but not great for travelling and seeing 'the real India'. We had originally itended to stay for 5 days. After breakfast in one beach resturant, politley refusing pleads to visit every shop on the high street, a swim, lunch in another resturant (exactly the same as the first), walking the length of the beach and then onto the next beach, we realise we have done everything there is to do and plan to leave as soon as possible. In the evening we watch the film 'The Life of Pi' in an outdoor cinema and the next day book the over night bus to Hampi. It leaves on saturday, so we have some time to kill. The next two days are spent swimming, reading, sunbathing in short bursts until the sun gets to hot and we have to run to the nearest bar, our feet burning on the sand. We eagerly plan the next few weeks. I feel guilty for wasting travelling time on the beach, and slightly less guilty for wanting to leave 'paradise' as soon as possible.

Above: Sunset

Wednesday 6 March 2013

The Train to Goa

We board the train with our rucksacks on our backs and only just fit through the doors. It seems fairly empty despite the difficulty we had getting tickets - at the hostel the website kept crashing and we were told to go to the station, at the station; "not possible madam, fully booked", and at the travel agents it is possible only for a huge booking fee. Eventually we get 'taktal' tickets, which seem to only be available the day before - for ' emergencies'. So we are very relieved when we find our bunks and our ticket is checked and deemed valid. The aisle is slightly off center. On the larger side of each section there are two sets of three bunks facing each other horizontally across the carriage. On the smaller side there are two bunks parallel with the aisle. The bunks are very narrow and there is not enough room to sit up on them. We are on the upper birth as we had been told that this was the best way to avoid being trodden on as people climb up.

As we set off chai and samosa sellers hurry up and down calling 'chai chai chai' etc, but are going too fast to get their attention. There must be some sort of secret signal. It is very cold although we thought we had booked non AC, so I wrap myself up in my brown 'Indian Rail' blanket and drift off. I sleep for the first few hours but I'm disturbed by the man in the bed across the aisle with the most offensive snoring. It is comical and disgusting at the same with a huge guttural intake that suggests that all the hocking and spitting doesn't actually do much good, and an actual whistle on the way out. I get up to wonder around the train. There are lots of families producing huge picnics from their bags in little Tupperware pots and spreading them out over their bunks. The first and second class cabins have only one or two tiers of bunks, but other than that are not much different from our sleeper class. The kitchen carriage is hot and noisy with pans wobbling around on a huge stove. Men are hurrying in and out with either boxes on their head full of sandwiches, samosas, omelets and dosas or carrying vats of tomato soup and chai. I am shooed away back to my compartment where I spend the 12 hour journey reading, playing cards and hanging out of the big open doors between carriages to see the view.

Train arrives at Marago two hours late. It is now 20:30 and we have another hour's bus journey before we get to Palolem - if there any buses. I am looking forward to waking up on the beach and don't really want to spend the night in the city. As we walk down the platform we spot two rucksack laden girls asking a porter about buses and and we ask if they happen to be going to Palolem. They are and so we share a taxi for the 40 minute drive. The main (and only) street in Pallolem is lined with shops, cafes and, worst of all, men who work for commission by bringing you to the hostel, beach hut or guest house they work for. We refuse all offers as the commission gets added to our bill. We walk down the beach for 5 minutes or so, which is very difficult with our rucksacks, and eventually give into a young man with good English who mentions some beach huts listed in our guide book. He says it is his family business, he doesn't work for commission, and there are lots of other travelers there. The latter is at least true. The two leathery European hippies strung out on hammocks and say that the 'Brown Bread Coco Huts' as they're called, are "really cool". The hut is clean, has a fan, mosquito net, attached bathroom, and is 100 meters from the beach. It is now nearly 22:00 and it will do for tonight. As I fall asleep I am still rocking from the train and I can hear the sea.

As we set off chai and samosa sellers hurry up and down calling 'chai chai chai' etc, but are going too fast to get their attention. There must be some sort of secret signal. It is very cold although we thought we had booked non AC, so I wrap myself up in my brown 'Indian Rail' blanket and drift off. I sleep for the first few hours but I'm disturbed by the man in the bed across the aisle with the most offensive snoring. It is comical and disgusting at the same with a huge guttural intake that suggests that all the hocking and spitting doesn't actually do much good, and an actual whistle on the way out. I get up to wonder around the train. There are lots of families producing huge picnics from their bags in little Tupperware pots and spreading them out over their bunks. The first and second class cabins have only one or two tiers of bunks, but other than that are not much different from our sleeper class. The kitchen carriage is hot and noisy with pans wobbling around on a huge stove. Men are hurrying in and out with either boxes on their head full of sandwiches, samosas, omelets and dosas or carrying vats of tomato soup and chai. I am shooed away back to my compartment where I spend the 12 hour journey reading, playing cards and hanging out of the big open doors between carriages to see the view.

Views of and from the train

Train arrives at Marago two hours late. It is now 20:30 and we have another hour's bus journey before we get to Palolem - if there any buses. I am looking forward to waking up on the beach and don't really want to spend the night in the city. As we walk down the platform we spot two rucksack laden girls asking a porter about buses and and we ask if they happen to be going to Palolem. They are and so we share a taxi for the 40 minute drive. The main (and only) street in Pallolem is lined with shops, cafes and, worst of all, men who work for commission by bringing you to the hostel, beach hut or guest house they work for. We refuse all offers as the commission gets added to our bill. We walk down the beach for 5 minutes or so, which is very difficult with our rucksacks, and eventually give into a young man with good English who mentions some beach huts listed in our guide book. He says it is his family business, he doesn't work for commission, and there are lots of other travelers there. The latter is at least true. The two leathery European hippies strung out on hammocks and say that the 'Brown Bread Coco Huts' as they're called, are "really cool". The hut is clean, has a fan, mosquito net, attached bathroom, and is 100 meters from the beach. It is now nearly 22:00 and it will do for tonight. As I fall asleep I am still rocking from the train and I can hear the sea.

The view from our beach hut in the morning.

Early Morning in Mumbai

Having picked up Alex from the airport on Monday and introducing her to Mumbai via a hectic train ride, we decide to head to Goa on Wednesday morning. The train leaves at 5:45 and the station is a 10 minute walk away but we leave our hostel at 5 just to be on the safe side. It just beginning to get light and its interesting to see the streets at this time. It is less busy, cooler and the people who are awake are nicer and stop to say good morning. At one point a GIANT rat runs across our path and hops over some people who are asleep on the pavement, of which there are a lot. Most have a little mat and are covered completely in shawls like an Egyptian mummy, although some are just on piles of newspaper or plastic bags. Like a bed in a hostel dorm, it seems that what ever space they do have is theirs, and we are careful not to step on the mats. All the stalls selling bags, watches, t shirts, locks, perfume, phone accessories and pretty much anything else you can think of in the day are covered over with tarpaulin and their owners are sleeping on top of them. We stop to buy some water and bananas out side the station and then go and find our train.

Sunday 3 March 2013

Dharavi Slum

On my third day in Mumbai I go on a tour of Dharavi slum. Initally I am uncomfortable with the idea of paying to be shown round a slum as though it were a zoo. My hostel tells me that 60% of the money I pay goes to the slum, 30% to the guide, and only 10% to the hotel. Im not completely convinced but it makes me feel a bit better.

Our guide meets us (there are 12 all together) outside the hostel and says we will be taking the train. His name is Devdan, he is 17 and lives in Dharavi. He tells me that he does between five and seven tours a week. The money he gets pays for his studies in accounting. The train takes about half an hour. It has metal seats and big open doors which people hang out of some what unnecessarily as there is plenty of room inside, but maybe it is cooler that way. On the way several blind beggars wonder up and down the asiles singing for money. When they get to the end, the person they bump into turns them around and they carry on. At one point we hear a loud clap as a young woman in a sari enters the carridge and blesses every passenger before clapping some more and coming around again asking for money. The girl next to me, who has been travelling in India for three months, tells me that the woman is a hermaphrodite, and considered lucky.

When we get to our stop we cross the bridge which gives us a view of the slum. It is not quite as good as the view you get from the window of a plane, of which the undercarridge almost skims the corrugated iron and tarpaulin roofs threatening to knock the whole lot over, as you land in Mumbai airport. Devdan tells us that the slum is one square mile and home to one million people, with one loo to every fifteen thousand people.

It turns out that my concerns about paying to view people in poverty were unnecessary. As we are led off the main street running though the centre of Dharavi (where there are shops, resturants and even banks) and into the narrow alleys we see some of the estimated fifteen thousand one-room busissness and factories that run out of Dharavi. My guide book tells me that a quarter of a milliom people are employed in these factories amd they turn over $700 million a year. The biggest of these businesses is waste recycling, particually plastic. We visit one factory where two men are sorting out different coloured plastics and another is putting them into a chipper without much concern for his fingers, although as far as I could see he still had them all. Every now and then a group of children come in carrying huge bags of plastic, mainly bottles, on their heads to be sorted. I think about the huge collection of water bottles I have already collected and disgarded and feel slightly less guilty. We are told that the chipped plastic is then sent to another factory to be made into rope for jewellery. We see lots of other factories including a leather works and textiles, both of which have huge industrial machines crammed into tiny rooms which had probably been built around them as they would not have fit through the tiny doors or though the alleys.

Next we go into a residential area. Here the alleys are even narrower and enclosed over head but so low that even I have to duck to avoid hitting my head or walking into the low hanging electrical cables. Devdan tells us that all of Dharavi has 24hr electricity and that every child goes to NGO schools until the age of sixteen. There are women and children sitting on door steps all of which are spaced about a meter apart. The women are all beautifully dressed in colourful, bead and sequined trimmed saris and wear lots of jewellery. There are less than half the number of women on the streets as men, but the homes are cool and quiet, so this seems to me a good idea rather than forced domesticity. Maybe they don't think so, but they seem to find it funny that we would want to walk around in the middle of the day.

We weave our way along the paths for several minutes until we find ourselved out into a big open space piled high with litter, topped with playing children. Devdan tells us that the area had been cleared as the start of a $40 million redevelopment programme. In return for eviction and the demolotiin of Depharavi, residents would get rooms in the new appartments, hospitals and colleges, there is almost universal objection. A family would get 255 square feet, less than many have now, and there would be no room for their businesses. Instead of a brand new development, residents say they want simple improvement of the conditions they already have.

Our tour ends at one of the locations the film 'Slumdog Millionaire' was filmed. I don't recognise it. Devdan tells us that lots of people living in Dharavi did not like the film as it showed none of the shops, businesses and schools but 'only the very very bad bits'. I agree. My preconception about the "largest slum in Asia" as a miserable place full of desperately poor people with no occupation other than begging was completely wrong. The residents said they felt lucky to live there rather than on the streets, everyone had a home, electricty, a job, education and a community.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)